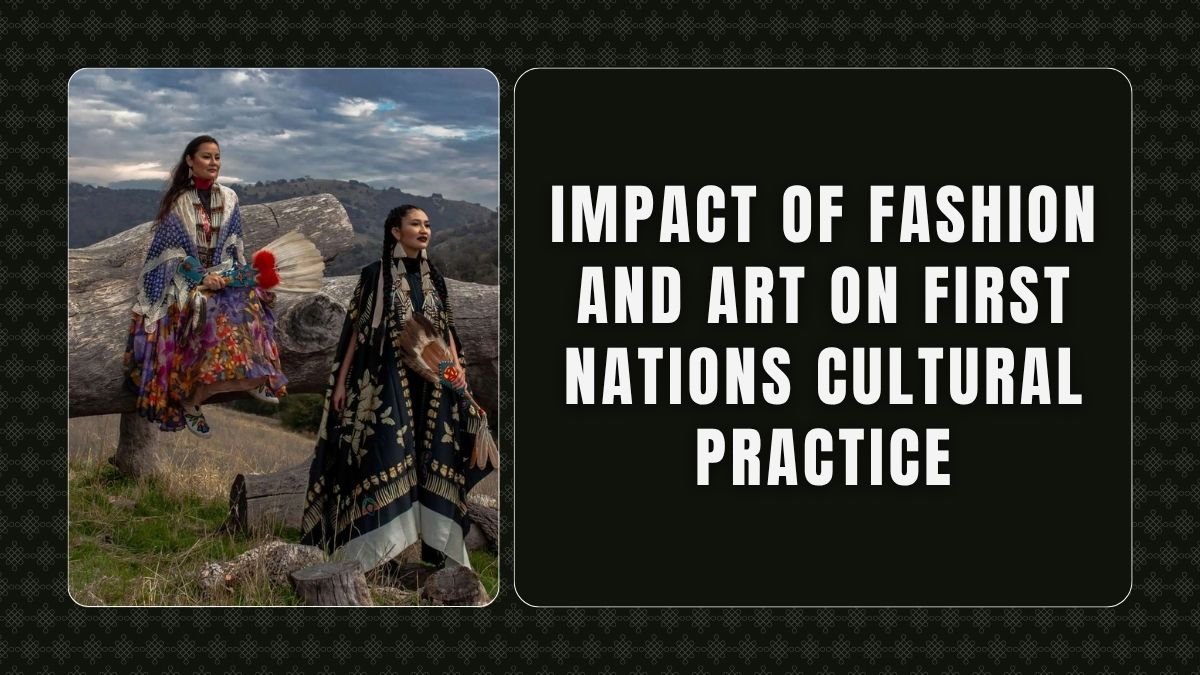

When we talk about fashion or art, we usually think of it as beauty or grace. But have you ever thought that fashion and art are not just a way of showing off but can also be a way to express a community’s soul, its suffering, its history and its identity? Especially for First Nations communities, who have suffered centuries of neglect, colonial exploitation and cultural erasure, fashion and art have become a process of not just creativity but healing and regeneration. These mediums not only revive the traditions of their ancestors but also keep the flame of self-esteem and identity alive from one generation to the next. This article delves deep into how fashion and art are becoming the basis of First Nations cultural practice and mental, spiritual and social healing.

Traditional art and fashion: A way to relive fading memories

The cultural heritage of First Nations communities is thousands of years old, in which colors, fabrics, shapes and symbolic designs play an important role. It’s not just decorative—each pattern, each piece of clothing tells a story, commemorates an ancestor or revives a ritual, festival or belief. For example, kangaroo skin cloaks, once worn by elders, are returning to the scene through emerging fashion designers, or shell necklaces, which were part of a young person’s coming-of-age ritual, are returning to families as emotional heirlooms.

The culture that colonial powers tried to suppress as ‘uncivilized’ in the past is now standing tall on modern platforms in the form of art and fashion. When a First Nations youth creates his own clothing with traditional designs, he not only connects with his roots but also strengthens the collective consciousness of his community. This cultural renaissance ignites a flame of self-esteem—one that is passed down from generation to generation.

Healing through Fashion: A Journey from Body to Soul

Many First Nations people have suffered deep emotional and spiritual trauma due to colonial exploitation, forced separation of children from their families, language loss, and land dispossession. When they reconnect with their traditional arts and fashion, the connection is not limited to clothing or colors—it opens a path to emotional healing, self-acceptance, and cultural pride.

For example, many community-based workshops that teach youth how to weave traditional fabrics, beadwork, dye, or paint have shown that youth who engage in these activities have improved self-confidence, social bonding, and emotional stability. These activities are not just for fun or skill development, but they also create healing circles in the community. In the process, participants feel pride in their identity, connect with old memories, and sometimes find inspiration to heal from emotional pain.

Anti-colonial: Clothing can also become a voice of resistance.

Another important aspect of art and fashion is anti-colonialism and the reframing of historical discourse. Many First Nations designers have incorporated symbols into traditional fashion that were once denigrated by colonialism—such as military uniforms, prison clothing, or church symbols. Now these same symbols return in a new context—where they become symbols of resistance, critique, and liberation.

For example, when a designer brands a garment “Stolen Land” or presents traditional totemic symbols in a style that was once described as ‘barbaric,’ he or she is not just designing—he or she is rewriting history. This protest is not just done with words but with colors, clothing, and platforms, a reminder to society that we will now tell our own stories and shape our own future.

First Nations fashion resonates on the global stage.

Today, First Nations fashion is no longer limited to its community. It has become a global movement, with Indigenous designers showcasing their culture through their designs at prestigious stages around the world—such as Australian Fashion Week, New York Indigenous Fashion Week, and Paris Ethical Fashion Week.

Names like Dorothy Grant, Victoria Kakuktinniq, and Loren Aragon are pioneers of this wave, reinventing traditional designs in a modern format, transforming them into not just fashion, but living heritage. These designers weave together futuristic imagery, traditional symbols, and community spirit in their designs, transforming fashion into a powerful social statement.

Sustainable Development and Self-Reliance: From Clothing to Economy

Along with cultural healing and self-esteem, fashion has also opened new doors of economic opportunity for First Nations communities. With the demand for traditional designs and crafts on the rise, young fashion entrepreneurs, women, and artists in many communities are becoming self-reliant. They not only create income for their families but also spread culture through their products.

In addition, First Nations fashion is traditionally sustainable—using every part of the garment and local materials. Concepts like sustainability and zero waste are deeply connected. That’s why, as the world grapples with the ills of “fast fashion,” First Nations fashion offers an alternative model—one where nature, culture, and craftsmanship are in harmony.

Conclusion: Art and Fashion—Identity, Healing, and the Light of the Future

The role of fashion and art in keeping cultural heritage alive, healing mental and spiritual wounds, and strengthening community identity is invaluable to First Nations communities. These tools are not just expressions of creativity but also healing of the soul, resistance to society, and reimagining the future. The work of Treena Clark and other researchers has proven that when you connect with your roots, wear your culture, and represent it proudly—you don’t just wear a costume, you live history, culture, and spirit.

So, through fashion and art, First Nations culture is not only preserving the past but also creating a path of justice, respect, and self-reliance for the future.